As a follow-up to our tribute to the late Prince Philip and his signature double-breasted blazer, here’s a lengthy feature I did for The Rake back in 2014. It should appeal to all those with a general interest in menswear, as well as all of you now contemplating a DB blazer. Pictured above is Fred Astaire from “Funny Face,” in which he sports a double-breasted grey flannel suit with blue oxford buttondown and bit loafers, while at bottom is a blazer from J. Press. In between is yours truly in 1988 on the night of high school graduation, with big ’80s hair and a pointed influence of Tom Wolfe circa “The Bonfire Of The Vanities.” — CC

* * *

Make Mine A Double

By Christian Chensvold

The Rake, issue 32

One of my more notorious contributions to the family photo album is a shot of me celebrating high school graduation in a double-breasted cream and tan checked silk sportcoat paired with a brown and white dot tie, looking every bit the preposterously precocious popppinjay.

I remember precisely where I got my inspiration. A few months earlier “Wall Street” had come out, and the costume that made the biggest impression on me was not one of Gordon Gekko’s power outfits. Gekko was fascinating, but I identified with Charlie Sheen’s ambitious young character, Bud, and the film’s sartorial apex comes when Gekko takes Bud under his wing — and sends him to his tailor. In the following scene Bud struts cavalierly into the office, engages in extra-cocky badinage with the secretary, and gives the general impression of a man who’s found a secret elevator to success while the rest of his peers are on a treadmill going nowhere. And it is a double-breasted suit that symbolizes Bud’s ascendance.

I remember precisely where I got my inspiration. A few months earlier “Wall Street” had come out, and the costume that made the biggest impression on me was not one of Gordon Gekko’s power outfits. Gekko was fascinating, but I identified with Charlie Sheen’s ambitious young character, Bud, and the film’s sartorial apex comes when Gekko takes Bud under his wing — and sends him to his tailor. In the following scene Bud struts cavalierly into the office, engages in extra-cocky badinage with the secretary, and gives the general impression of a man who’s found a secret elevator to success while the rest of his peers are on a treadmill going nowhere. And it is a double-breasted suit that symbolizes Bud’s ascendance.

“Wall Street” was released at a time when the double-breasted suit flourished as a sartorial distinguisher amid the competitive national fervor for upward mobility known as the Big Money ’80s. Because the DB button stance has things added to it — fabric and buttons— it is traditionally been viewed as classic. In contrast, the sleek postwar look, with narrow lapels, trousers and ties, is modern, and it’s impossible to imagine icons of midcentury style — The Rat Pack, Cary Grant in “North By Northwest,” Connery as Bond, Marcello in “La Dolce Vita,” JFK in the White House — in anything but single-breasted suits.

But today no single silhouette or lapel width dominates menswear as in decades past. And when it comes to the double-breasted jacket, the line between classic and modern is disappearing. Digital fashion plates such as Lino Ieluzzi are wearing the DB short and fitted, conveying panache more than power, individual swagger rather than group authority, and sun-drenched holiday rather than gloomy shareholder’s meeting. Likewise, tailoring and design houses are updating the fit of double-breasted jackets. Together, purveyor and end user are heralding a resurgence of the double-breasted by lint-brushing away the dust of the past.

If you already wear double-breasteds, perhaps it’s time to rethink proportion and styling, opting for a more modern cut, or wearing a jacket tieless to some dimly lit nocturnal event. And if you don’t wear DBs, allow us to change the way you look at them. Although I embraced the DB early, I drifted away from it for over a decade until another cinematic example changed my point of view. But more on that later: for now, let’s learn the nuts and fabric bolts of this most elegant of cuts.

BUTTONS & BEAUX

The double-breasted suit traces its lineage back to the 18th century, where it likely derived from the military tunic, which was wider at the top to accommodate the broad chest and wide shoulders of the male torso. If unbuttoned at the top and rolled back, the tunic would approximate two pointed lapels while still overlapping at the waist. The double-layered tunic would have provided soldiers with warmth as well as an extra layer of protection against any rapier that happened to be thrusting their way. Speaking of which, double-breasteds overlap from the left so that a right-hander won’t get the pommel stuck when withdrawing a sword from his left hip.

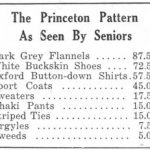

When the lounge suit emerged in the late 19th century, it derived from sports jackets used for riding, shooting, rowing, golf and so forth, and such jackets were always single-breasted. It wasn’t until the 1920s that the modern double-breasted suit, blazer and odd jacket emerge on such prominent style leaders as The Duke of Kent, Lord Mountbatten and the Prince of Wales, all of whom had military backgrounds. “Most of those guys were navy men,” says author G. Bruce Boyer, “and they were all used to wearing double-breasted navy reefer jackets in their youth, so I think they started having their mufti made like their uniforms.”

The double-breasted’s pronounced V-shape at the chest emphasizes the inverted pyramid of the male torso, a triangular shape echoed in the DB’s poignard-pointed lapels. Notch lapels, along with a single rear vent, are considered gauche tamperings with an established form and The Rake admonishes avoiding them at all costs. Eight-button and two-button fronts exist but are highly offbeat, so the DB generally comes with four or six buttons. A four-button that fastens on the lower button is abbreviated 4 x 1, while a 4 x 2 rolled to the lower button, with the top buttons place directly above the bottom, is known as the Kent, for the man who popularized it. A six-button can have up to three fastening options and is therefore referred to either as a 6 x 1 or 6 x 2, with some hairsplitters even employing the term 6 x 1/2. Given the option on which to close, fastening the middle button generally provides a classic and formal look. A 6 x 1 sometimes has all the buttons placed on the diagonal, with the only choice of buttoning the bottom. While some find this nonchalant, others think it looks dated, reeking of the ’80s and ’90s, while others will say that the bottom four buttons should always be in line. Buttoning both the upper and lower on a 6 x 2, most clothes-wearing men would agree, looks uptight.

When creating a double-breasted suit, a bespoke tailor will typically place the bottom buttons even with the top of the pockets, then go up from there in proportion with the client’s torso. Horizontally, there should be at least a couple of inches from the pocket to the button, as it would look ill-fitting were the left side to overlap so far as to reach the right-side pocket. As for length, it’s a good idea to wear the double-breasted a tad shorter, lest you look mummified in fabric both widthwise and lengthwise.

The DB’s inner anchor buttons keep the jacket front flat, and there can be either one or two inside in the case of 6 x 1 and 6 x 2 jackets. You can also leave the anchor button undone. “Often Astaire wouldn’t fasten the inner controlling button and just sort of let the front of the jacket collapse,” says Boyer, “and that’s a great sprezzatura look.” The opposite approach — fastening the anchor button but not the outer, letting the jacket front flap around — is one of the sartorial gimmicks of late-night American TV host David Letterman, and should only be attempted by premier league smart-alecks. Choosing to unbutton one’s jacket when seated is natural to some, crude to others. Joseph Morgan of London’s Chittleborough & Morgan advises opening a DB jacket when seated, while Boyer, in a chapter from on double-breasteds from his book “Elegance,” recounts Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. telling him he couldn’t stand to see an unbuttoned jacket, saying, “All that flapping about, with the tie and shirt hanging out, I find rather sloppy.”

As the double-breasted is an established form, there’s more danger in toying with the basic architecture than the context and style in which it’s worn. DB blazers may be worn with shorts in certain social situations in a place like Bermuda, and a DB suit can certainly accommodate black turtleneck at a gallery opening, though you may be expected to say something insightful. Certain punctilious pundits may argue that the DB inherently carries certain height and weight requirements. While we disagree, it’s certainly the case that a 6 x 1 button stance will de-emphasize the waist, elongate the front, and play down girth, should any of those illusions be desired. If anything, the DB’s sharp V shape is slenderizing, so forget that tired canard about never wrapping a stout man in too much fabric.

DIFFERENT FOLKS, DIFFERENT STROKES

The 1930s, the so-called Golden Age of Menswear, is virtually synonamous with the double-breasted jacket. The ’30s trifecta of style inspiration — the Duke of Windsor, Old Hollywood, and Apparel Arts illustrations — show the DB in myriad fabrics and styling combinations. But while today’s tailors may look to the past for inspiration, they’re not necessarily copying the cut. Pointed ski-slope-wide lapels may tempt you to think the DB requires strong shoulders, but today the conventional DB power suit is being challenged by sleeker, softer and hipper options. Case in point, Paul Stuart’s Phineas Cole collection, American elegance at its apex.

Although Paul Stuart is located on Madison Avenue, epicenter of the American natural shoulder, the Phineas Cole shoulder has nothing to do with the tradition of Brooks Brothers and the Ivy League Look. The Phineas cut has a soft and sloping shoulder, but it also has a high armhole, tight chest, and sharply suppressed waist. The rounded shoulder echoes the sculpted waist while contrasting with the sharp lapels and deep V of Phineas Cole’s double-breasted models. “I got far away from that old Wall Street power look,” says designer Ralph Auriemma, “and kind of invented a sleeker, softer, more elegant silhouette. It’s a different kind of power look, more sophisticated.”

In London, Chittleborough & Morgan show that the English and Americans are divided by a common tailoring language, with similarities as well as differences. “Our double-breasted design is very formal,” says Joseph Morgan.” The button-two-show-three model can be fastened at the waist and bottom button, though if you wish you can just fasten the lower to have a long lapel roll. We cut a straight shoulder line with a small armhole, giving a long line to the waist. Our model makes one stand a little more erect; the clothes are built and tailored.”

In Paris at Cifonelli, jackets are engineered to soften the V at the chest for the signature house look. Demand is currently up, especially for the low-fastening 6×1 with diagonal button placement. “Our DB suit is absolutely unique in terms of style and work,” says Lorenzo Cifonelli. “For the lapels, we cut the fabric to make it slanted to give them a curving shape. A double-breasted jacket always need to be really open around the top and collar of the shirt. You can easily recognize a Cifonelli DB by the wide and curved lapels, with peaks are particularly high and straight.” The Cifonelli double-breasted is also a tad shorter than tradition would dictate, and has a stronger rather than drapey shape. “A lot of people think the double-breasted is old-fashioned,” says Cifonelli. “That’s the main problem if it is not well cut.”

In Naples at the headquarters of Rubinacci, the attitude is a bit more old-school — at least in the eyes of the firm’s patriarch. “The DB is more specific for a formal business suit,” says Mariano Rubinacci. “We recommend it in solid or chalk stripe flannel, or for the more sophisticated, in beige gabardine or Prince of Wales plaid in flannel. Usually we make them with welted pockets, sometime with change/ticket pocket, with a six-button front and we prefer with no vents. We only make the famous navy blazer with sporty patch pockets, strong double stitch and side vents.”

But there’s always a generational difference. “Double-breasted is my favorite style at this period of my life,” says fashion-leader son Luca Rubinacci. “I like wearing it in a more sporty way, buttoned at the last button, and the lapel has to break there. This way you can have a more relaxed look, with the jacket more open in the front. For me, a soft shoulder, camica spalla, and double vents are required. I like wearing a DB either as a suit or odd jacket mostly during winter, with a cashmere turtleneck underneath.”

RULES TO LIVE BY — OR BREAK

To be an intelligent and stylish dresser, one should neither stiffly adhere to rules and traditions nor ignore them entirely. Both are pitfalls, and in the interest of taking the middle path, here are a few things to be cognizant of when accessorizing the double-breasted suit or jacket. Some will love and some will hate a turtleneck under a double-breasted suit (which was popular during Hollywood’s Golden Age), but it certain has more adherents than crewneck over a dress shirt. Casual slip-ons, such as driving or penny loafers or Belgian Shoes, along with buttondown-collared shirts and cardigans under a DB suit, all carry moderate to heavy risk. A jacket that clearly belongs to a suit but is worn as an odd jacket carries high risk, though there’s a certain stylish nod to the ’30s in wearing a navy flannel chalk stripe, say, with white trousers, assuming a sporting activity or body of water is nearby. For a dramatization of this, see the film adaptation of Agatha Christie’s “Evil Under The Sun.”

Traditionalists will favor French-cuffed shirts with DB suits, along with full-cut pleated trousers, likely cuffed. Those with more modern sensibilities will simply do the opposite: barrel cuffs, flat-fronts and no cuffs.

For eveningwear, the double-breasted dinner suit bring elegance as well as simplicity. No need to wear a waistcoat nor those horrible cummerbund girdles requiring constant adjustments each time you move. According to Boyer quoting Fairbanks, the DB dinner jacket without waistcoat was yet another fashion made popular in the ’20s by the Duke of Windsor. And while notch lapels are always gauche, shawl lapels for evening are fine, especially on such baroque fare as velvet dinner jackets with frogging.

How much double-breasted is too much? For starters, a double-breasted three-piece suit with double-breasted vest. However, the choice of overcoat is an interesting one. Can one not wear one’s favorite fraying polo coat over a DB suit? “I think it’s a bit much,” says Boyer, “but is still perfectly OK.”

And while nowadays all hats sadly carry moderate risk of anachronism, a proper homburg or fedora will best complement a double-breasted suit, while a porkpie will have you looking like Dexter Gordon circa 1947 (not a bad thing to some), and a floppy eight-panel newsboy can conjure up Robert Redford in “The Sting,” or Depression-era swells shooting craps on the sidewalk.

EN FINALE

Oddly enough, a few weeks before receiving this assignment I’d just rewatched Fred Astaire in “Daddy Long Legs.” Made in 1955 when the DB was horribly out of fashion, Astaire, who loved the DB, fashioned a couple of outfits in which he wears a short 4 x 1 odd jacket with his beloved grey flannels, plus bright socks, suede lace-ups, satin tie, and, if I recall correctly, a buttondown oxford. It was wonderful gesture of individual style that got me looking at the DB in a new light, longing to replicate Astaire’s played-down styling.

And that’s really what’s best about our revered style icons. They transcend the vagaries of fashion and demand constant reassessment and fresh points of view. No doubt the same will happen one day to Gordon Gekko’s big-money look. But at this particular moment in time, it seems wiser to strip the DB of any kind of inherent power and rechannel the power into you. For mastering the double-breasted is not really about expressing external signals, but inner wisdom.

I don’t intend to be critical, but I disagree with “A jacket that clearly belongs to a suit but is worn as an odd jacket carries high risk…”

In the latest (April 2014) issue of GQ, Jim Moore writes about the resurgence of the DB odd jacket: “The DB sports jacket which can be treated with all the love and care of a jean jacket…team it with everything from a tie to a tee.”

Contrasting jacket and trousers (spezzato) is a very Italian way to make wearing a formal jacket more casual and nonchalant.

to me, please correct me if Im wrong, but the DB always seemed like a tall man’s jacket-I’m 5 foot 6 and I feel like I’d look silly in one

@dgb

You are absolutely right.

I’m 5’8″, and it not only makes one look shorter, but wider.

Only if is cut badly.

This is the problem with double breasted: he must be perfectly cut and balanced,or is ugly.

But when is well cut…oh boys…is the king! none jacket is so elegant and smart!

Hate em just as much as leisure suits!

I have a number of DB suits and blazers. Must keep buttoned always; otherwise looks sloppy. BTW, 2014 GQ-and Esquire-illustrate how NOT to dress.

Very nice cover picture, July issue, of Charles Dance in white/cream bespoke suit!

My guess is that Messrs. Boyer and Press would advise us that the decision on whether to wear a double-breasted navy blazer is not to be taken lightly.

Dig that crazy hair. I had a hair helmet back in the 80’s too. Those were the days. No real responsibility. Hot girlfriends. Cigarettes. Ban de Soliel for the San Tropez tan. Beach parties. Heineken in Solo cups. Magnum PI shorts. No bullshit flu or face diapers. Is Elon working on a time machine?

Will

It’s perhaps unfortunate that the DB is, here (in the American sartorial context) perceived as “a bit too much.” Garish, vulgar, ostentatious. Like the Rolex (or equally showy watch), bit loafers, the voluminous mansion, and luxury cars, its proponents, eager like a peacock to spread feathers, will not be deterred.

Yet another example of how understated New England WASP style bumps up against (often runs counter to) Anglophilia, and, more generally, stylistic nods to European royalty/aristocracy.

And yet it’s interesting how often the two are so confused. Exhibit A is that Muffy gal, who tries to merge nouveau riche, luxe Anglophilia (yes, for God’s sake, we know by now that Cordings makes good stuff) with highbrow Gold Coast Connecticut culture (looky— another restored MG in the yacht club parking lot!)

It nudges the gag reflex. What happened to old WASP understatement??

S.E.

Apparently, like many of us, you still follow Muffy’s blog.

Be careful – not to mistake the occasional spectator for a fan.

Nor bemusement for admiration.

S.E.- I’d enjoy reading an article on your perception of classic low-key NE WASP lifestyle. You’ve made several references to your observations over the years in the comment section. Please do a deep dive for us!

I think that the DB style is greatly underrated. But I’m thin and fit – about the same weight as when I did triathlons in my 20s. It might not work as well on the typical American man, who’s close to 200 pounds.

Haven’t thought seriously about a DB sport coat, but I’m fairly sure that I’m not a fan of the DB SC without a tie look. Or the unbuttoned DB look. But then I’m a middle-aged guy counting down the number of months until I retire. If I was back in college I might be doing those, not yet having the better judgment that often accompanies a few more years of age.

As mentioned above, my concern at this point in my life is anything that would make me look wider would be avoided.

I find that the extra cloth around the middle makes the DB hotter and more uncomfortable in the summer.

DB’s are ok – though the Scholte and Scholte-inspired drape that worked so well on Astaire and the somewhat more fitted Ivy versions have now largely disappeared, at least from RTW.

Duffel coats should still be 3-4 sizes too large, though. That’s timeless.